“…the children have moved on, leaving creators lagging behind a bit.”

– Makoto Yamashina, Bandai President

It’s difficult to pinpoint the precise moment that the gunpla boom ended, but by 1985 the real robot goldrush was coming to an end. Model kit and toy companies had spent the last four years funding new giant robot TV shows in an attempt to replicate the success of Mobile Suit Gundam [1979], but none of them had found that degree of success. By 1985, toy and model manufacturers were looking at dwindling returns, viewers were burned out on real robots, fans of the original Gundam were getting older, and a new toy called the Nintendo Famicom was the new must-have item for kids.

By the beginning of 1985, the company behind Gundam’s popular plastic model kits and a great many other model kit series and toy lines had begun to look in new directions, many of which would leverage the older fans that had first propelled Gundam to success. This generation of fans was getting older, going into the workplace, had more money to spend but also had changing interests. In 1985, those new directions began to take shape and in doing so, charted a new course for the company.

1985 was the year that Bandai launched, in no particular order: the production of an all-new feature film, a new hobby publishing division, a serious attempt at finding success in the direct-to-video anime market, and the first new Gundam animation project since the compilation movies of the original series. These plans were not the summation of the entire company–Bandai is big–but they did represent, at least partially, how the company was starting to look at older customers and new opportunities. Together, these plans and projects represented Bandai’s attempt to keep hold of an aging customer base, branch out into new markets, and turn their most successful show into a tentpole franchise. In almost every regard, they were successful, although not always as expected.

A GRAND EXPERIMENT

“I didn’t want them to make a movie people like us would understand.”

– Makoto Yamashina, Bandai President

“It was [Shoji] Kawamori or [Kazutaka] Miyatake of Studio Nue who once said, ‘It’s easy to make supporting roles out of mecha, but it’s not easy to make main characters out of them unless they’re charismatic.’ To go along with that statement, we’d agreed pretty much that we didn’t need mecha in leading roles, and focused on creating supporting roles for them. That’s why we don’t have a single device that plays a leading role. Even the rocket is not a main character in the film.”

– Hiroyuki Yamaga, Director of Royal Space Force

The production of Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honneamise [1987] was the raison d’être for Gainax, the now-legendary studio having been created explicitly for the production of that film. Incorporated in December 1984, Gainax’s debut work was to be a wholly original film, produced with an unprecedented budget, staffed largely by very young animators and creators who had just broken into the industry in the post-Gundam wave of fans heading into the animation industry.

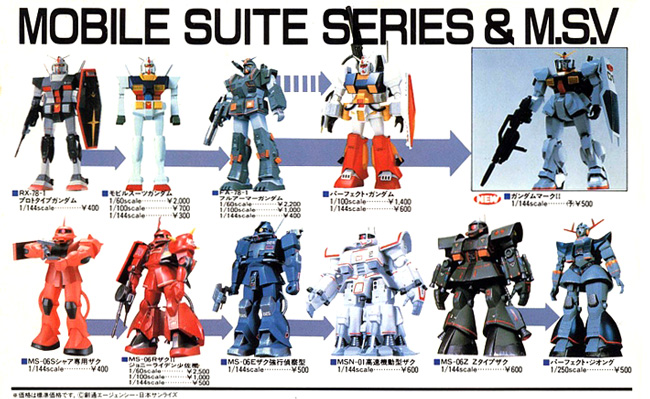

According to the film’s director, Hiroyuki Yamaga, the project stemmed from a proposal that the staff of Daicon Film presented to Bandai to make an anime based on the company’s Mobile Suit Variation (MSV) model kit series. The MSV plastic models were an extension of Bandai’s original Gundam model kit line, featuring a range of “never seen” designs from the One Year War that drew heavily on more traditional military aesthetics and more realistic colors. With a new Gundam series and a focus on the direct-to-video market on the horizon, it seems odd that Bandai wouldn’t want to blend the two, but Bandai had other ideas. In the words of Bandai President Makoto Yamashina, “We wanted instead to partake in a grand experiment entirely with our own concept, to be in complete control, and to make something original. We didn’t want to borrow someone else’s property to make a movie.”1

The film that Gainax and Bandai would create (with real production beginning, ostensibly, in 1985) was Royal Space Force. It was a meticulously crafted science fiction film about the burgeoning space program of a country on a planet that only vaguely resembled Earth. It was not a film that would be merchandisable in the traditional Bandai sense, that is, as toys and models.2 But Bandai was looking at other types of merchandise, because after selling the film itself in theaters, they could sell it as home video, as soundtracks, and as printed media. These were the types of merchandise older kids would want to purchase, and Yamashina, to his credit, seemed committed to the idea of appealing to these older youths even if he himself didn’t understand the film.

Yamashina’s commitment to letting a young, largely unproven staff, create an extravagantly funded movie explicitly for young audiences seems remarkable in retrospect. Almost charitable. In an interview in 1987, from around the release of the film, he emphasized that he didn’t understand it, didn’t want to compromise the vision of the creators, and boasted “If I were to say why [the film is remarkable], it’s because this is the first time a movie has been made by the younger generation for the younger generation.” The flip-side of this more charitable view is that as much as there were older anime fans looking for something relevant to their tastes, there were plenty of similarly aged anime fans that were getting into the industry and were easily exploited, too. It was the era when animators began to sleep in studios and take risks that older generations of animators wouldn’t. Speaking about that seismic shift in the animation industry in the wake of Gundam, legendary director Yoshikazu Yasuhiko said, “The feeling of ‘its great the younger generation has such momentum’ and ‘whoa, hold it just a sec’ came at me both at once.”3

Royal Space Force, was, ultimately, a grand experiment that didn’t shatter records. But it did create a new animation studio that would later work with Bandai again on the OVAs like Appleseed [1988] and Aim for the Top! Gunbuster [1988]. In the years ahead, Bandai Visual continued to produce big-budget theatrical films, like AKIRA [1988], Patlabor: The Movie [1989], and Ghost in the Shell [1995]. All three of those films were, of course, based on pre-existing properties.

A NEW TYPE OF HOBBY MAGAZINE

“Well, Bandai is a pretty large company. You might have an idea for a project, but it has to go through the filter of managing directors, the board of directors, and so on. By the time it gets through all that, the project is deadlocked. It makes it hard to even understand what projects you really want to do.”

– satoshi Kato, Chief Editor of B-Club

The first two issues of B-Club were published on November 15th, 1985. That magazine4, and the publishing division behind it, presented an all-new approach to enthusiast publishing and products that were in step with the growing otaku subculture. The magazine’s editor Satoshi Kato described the magazine’s formation as the result of the bureaucracy and glacial pace of decision-making in a company as large as Bandai.

From the onset, B-Club was intended to be a more responsive hobby magazine that catered to fan interests and involved them in the actual production of the magazine. Early B-Club promotional material billed it as a fan-driven publication and regularly solicited submissions in the forms of manga, articles, and custom model kit photos. In doing so, B-Club could both be reflective of what fans wanted but also quick to pivot as tastes changed. Like Royal Space Force, it also relied on the labor and creativity of a slightly older demographic that was growing out of giant robots on TV and regular plastic models and who were at the age to now produce new things themselves.

B-Club wasn’t just a magazine mook, though. In addition to serving as a publishing division (which saw a variety of books and comics published, almost always based on Bandai-sponsored shows, movies, or OVAs), the B-Club division produced their own model kits5. Unlike Bandai’s plastic model kits, B-Club’s offerings were garage kits, produced in low quantities primarily out of resin. Smaller production runs and quicker turnaround times meant that B-Club could cater to shifts in taste or more niche topics, like models based on Bandai-produced OVAs or upgrade kits for existing Bandai plastic models. Throughout its history, B-Club operated a dedicated shop and produced heaps of kits, but both the magazine and the shop shut down in the late ‘90s. B-Club was used as a label into the 2000s almost exclusively for upgrade kits for Bandai kits, but it no longer seems to be in use.

The closest analogy today would be Bandai’s Premium Bandai label, although that differs in both scope and scale. One also assumes that back in the day buying B-Club products was slightly easier than the latest P-Bandai releases. In truth, the effect of B-Club was probably larger than just that of a niche label, as it paved the way for Bandai to release product that wasn’t inherently tied to a current TV series or film. Bandai undertook that in earnest with the series-agnostic High Grade and Master Grade model kit series in the early 1990s.

For further information on B-Club, please read our article from earlier this year.

THE AGE OF SALE AND RENTAL

“We want to not only deliver originals through traditional sales, but through an established rental system. Bandai’s rental system will begin in October. Next year, we’re set to start producing original anime in earnest.”

– Shigeru Watanabe, Bandai Producer

“Everyone got really into Dallos because it was the first of its kind, but we can’t count on that in the future. We can have people watch for a low price at first. Then, those who really liked it can buy it if they wish. That’s the kind of sale-and-rental system we need to move forward with.”– Shigeru Watanabe, Bandai Producer

Bandai was the first company to get involved in direct-to-video animation when it released Studio Pierrot’s Dallos in late 1983. Originally pitched as a replacement for Minky Momo’s timeslot, Dallos was deemed too mature for Bandai’s Popy toy division and the robots were too “unsightly” for Bandai’s hobby division. Instead, they took a gamble on releasing it straight to video, thereby defining the original video animation (OVA) format and seeing some success as each of Dallos’ four volumes sold an average of 10,000 units6. That paved the way for other early OVA releases like Machikado no Marchen [1984] and Birth [1984].

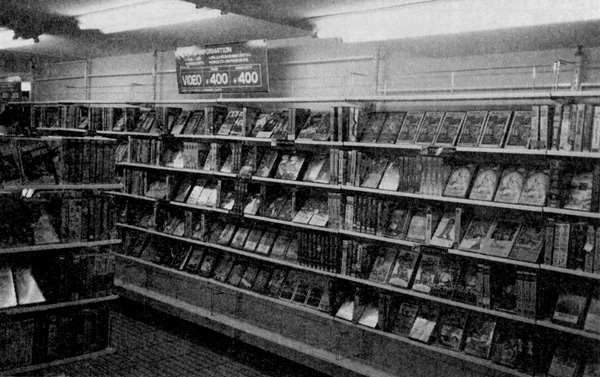

The first couple of years saw a disproportionate amount of pornographic anime released in the direct-to-video format, though that disparity soon disappeared as it became a more viable format for stories that wouldn’t quite work on TV or film. The format’s breakout hit was the ARTLAND/ARTMIC co-production Megazone 23 [1985], which like Birth and Dallos before it, had begun as a pitch for a TV show that never got picked up. While Bandai-produced OVAs wouldn’t really become noticeable until 1987 (a year that saw both Macross: Flash Back 2012 and Black Magic M-66 hit video store shelves), Bandai began laying the foundation for their OVA endeavors in earnest by late 1984, when they established their own legal rental system.

As the quote from Shigeru Watanabe above explained, Bandai’s efforts to seriously produce OVA content was to follow the establishment of their own rental system. If that seems backward, keep in mind the cost of video cassettes was high in the 1980s and even though more and more households were getting home video players, expecting customers to regularly shell out over 10,000 yen on a new video didn’t make much sense. Plus, “illegal” rental shops meant that Bandai wouldn’t be profiting from repeated rentals past the initial sale. Many of the first wave OVAs were original projects, which meant people didn’t know if they’d like the video and as a result, wouldn’t have been inclined to take such an expensive gamble.7

By establishing their own rental system, Bandai could ensure video sales via their network of franchised video stores and consumers could watch direct-to-video anime without having to sell the tapes outright. Both the Japan Video Association and Warner Bros. had their own legal rental system in place before Bandai, so they weren’t the first in Japan to try out this approach.

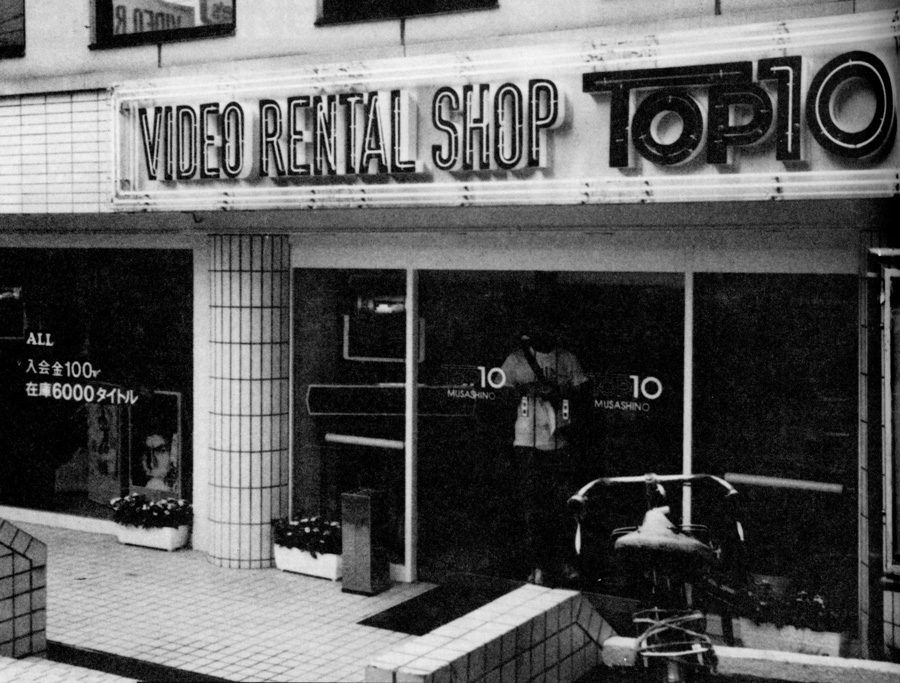

Bandai’s Frontier division ran a rental shop in Roppongi8 and later the company’s Network subsidiary opened similar shops in Kichijoji and Shibuya, but competition from video chain Tsutaya ensured they didn’t last long. Network was eventually absorbed by Emotion and at some point had a distribution agreement with Disney, though that doesn’t seem to have lasted very long, either. Bandai’s foray into video rental networks may not have taken off, but they remained committed to OVAs throughout the rest of the decade and into the ‘90s, with titles like Mobile Police Patlabor [1988] and Aim for the Top! Gunbuster [1988].

It’s worth noting that Bandai’s video push in the mid-’80s wasn’t exclusively focused on OVAs or even anime. Early offerings included select episodes of TV shows like Minky Momo or Future Boy Conan. Macross, in particular, received quite a few curated tapes like the Macross Special (episodes 1 and 2), the Lynn Minmay Special (episodes 4 and 27), and Macross Mecha Graffiti, a selection of mecha scenes from throughout the TV series. They also experimented with live-action video releases, such as the 30-minute live-action horror film Evil Heart, based on the manga of Kazz Umezu and released by Bandai’s Emotion label. Evil Heart, along with Guinea Pig: Devil’s Experiment9 [1985], has been credited with kicking off the popularity of splatter films, which flourished in the direct-to-video market.

BELIEVING IN THE SIGN OF ZETA

“I think many fans tend to see the whole Gundam story as one unified universe, but, frankly, I don’t think of it that way. In my own mind, from Zeta Gundam on, every Gundam story stands on its own.”

– Yoshiyuki Tomino, Director of Mobile Suit Gundam

Forty years on, it seems unfathomable that Bandai would go years without a major new installment of the Gundam franchise, but prior to Mobile Suit Zeta Gundam [1985], that’s exactly what they did. Perhaps, it was due to the continued sales of Gundam kits and the success of the MSV series, or perhaps it was because Bandai had other shows to sponsor and the concept of monolithic pop culture franchises pumping out new shows and films every year wasn’t the prevailing trend that it is today. Whatever the case, Bandai waited until 1985 to release a proper animated sequel to Gundam.

With the gunpla boom dying down, it wouldn’t be unreasonable to guess that Bandai might have also returned to the Gundam series because other shows they’d been backing simply didn’t move the same kind of product. Indeed, 1985 was the same year that Bandai’s competitor Takara backed off on show sponsorship, suggesting that the heaps of shows attempting to replicate Gundam’s success throughout the early ‘80s were offering diminishing returns. Bandai may have seen the solution as returning to the original success story. In doing so they created a massive multimedia franchise and confirmed that there would be many more Gundam spin-offs and sequels to come.

It’s worth noting that the approach to mecha design, and thereby model kit sales, changed a bit in Zeta Gundam. While the original series featured a variety of military units that fought alongside a handful of mobile suits, like planes, tanks, and mobile armor, Zeta Gundam focused much, much more on mobile suits. That’s a trend that continued through much of the rest of Gundam (although Mobile Suit Gundam: The 08th MS Team [1996] was an intentional callback to the combined arms approach of the original series) and the reasoning is likely a matter of simple model kit sales. Mobile suits sold best, kids didn’t want supporting units like planes and tanks, and mobile armor were too large to render in the typical 1/144th and 1/100th scales. This may also explain why Zeta Gundam featured around twice as many mobile suits as the original. More mobile suits meant more mobile suit model kits and toys.

Of all the moves Bandai made in 1985, the release of Zeta Gundam was arguably the most important. Today the words “Gundam” and “Bandai” are synonymous, but prior to 1985, it wasn’t necessarily assumed Gundam would be a long-lasting franchise. The first proper sequel helped ensure that there would be a lot more Gundam in the future, and following Bandai’s purchase of the animation studio Sunrise in the early 1990s, ensured that the series would be a key part of the company’s future.

’85 ONWARDS

In his explanation for the inspiration behind B-Club, Satoshi Kato complained of the glacial pace of new projects and ideas within companies as large as Bandai. While that was no doubt the case, the company’s experimentation in 1985 pointed towards a company that, at some level, had employees and executives aware of the nascent otaku generation and ideas on how to tap into its spending power. This wasn’t even all of Bandai’s new ventures for 1985; for example, they also started a new production venture in China that same year, the Fujian Toy Co. Ltd., to avoid issues with the fluctuating value of the yen and focus more on overseas production. Today about 90% of Bandai’s toy production is handled overseas.

These were decisions made by different executives across different divisions who found ways to branch out beyond models and toys in ways that appealed to the kids who had grown up with those models and toys. If these decisions prove anything, it’s that by 1985 companies were starting to hone in on otaku as potential customers and creators in their own right. In some ways, this marked a shift from the otaku underground being a DIY-driven subculture to a more prominent group of young fans that could be marketed to in a variety of ways. Bandai wasn’t alone in this respect; the OVA boom in the latter half of the ’80s saw major corporations like Sony and Pioneer have dedicated divisions focused on producing OVAs for a relatively small group of fans, for example. Otaku may not have entered the mainstream until the ’90s thanks to Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995), but by 1985 things were already heading that way.

Edit: I incorrectly had the co-founder of B-Club’s name written as Tomo Kato.

Special thanks to Karageko for continuing to translate obscure interviews from the ’80s, and both Renato Rivera Rusca and ehoba for digging up information about Bandai’s rental network.

Notes

- At this time the animation studio behind Gundam, Sunrise, and Bandai were separate entities. It wouldn’t be until 1989 that Bandai did, finally, produce an OVA based on Gundam, with Mobile Suit Gundam 0080: War in the Pocket. It was written by Hiroyuki Yamaga.

- The only models released around the time of the film’s release were a series of garage kits by the Gainax-adjacent General Products.

- This quote comes from an interview in the book included with Sentai Filmworks’ Venus Wars Blu-ray. It’s worth picking up!

- B-Club technically was not a magazine as it didn’t have a magazine code and was actually a regularly-issued mook (a portmanteau of “magazine” and “book”)

- Beyond the scope of this article a bit, but it’s worth pointing out that most B-Club kits probably weren’t produced in-house. People weren’t pouring resin in the office next to whoever was working on the layout of the next issue. In all likelihood, they contracted out much of their kit production. Early on, garage kit manufacturer Berg produced their New Cast Models, for example.

- That figure comes from an interview with Shigeru Watanabe in Animage, dated November of 1984. Curiously, he recently tweeted (and later deleted) that they’d produced 2,000 units for the first volume of Dallos and sold only 800 of those in the first six months after release. Getting reliable, hard numbers for 1980s OVA sales is difficult, to say the least.

- Soon enough spin-offs, sequels, and adaptions of popular TV shows and manga began dominating OVA shelves.

- Named Top10, this shop later ran afoul of the MPAA for renting out US imports.

- The Guinea Pig films were a series of six direct-to-video horror films with a particular focus on gore and depravity. Created by manga artist Hideshi Hino, the Guinea Pig films are best known for being found amongst the video collection of noted “Otaku Murderer” Tsutomu Miyazaki, leading to the suggestion that the films may have inspired the murders he committed.