Over on the Internet Archive, the Otaku Archive (spearheaded by Anime World Order co-host Gerald) has been uploading scans of documents from ‘80s and ‘90s anime fandom, including club newsletters and most recently, finished up a complete run of Animag magazine. From a historical perspective I’m not sure how much usable information you’ll find in those old newsletters—from clubs like the C/FO, Panime, and Boston Japanimation Society—but the vibes are immaculate. If you’ve ever wondered what it was like trading tapes and watching raw anime in an era when hauling your VCR to meetings was almost a necessity, well, look no further. There’s a lot to dig into and it’s nice to see these bits of fan history preserved.

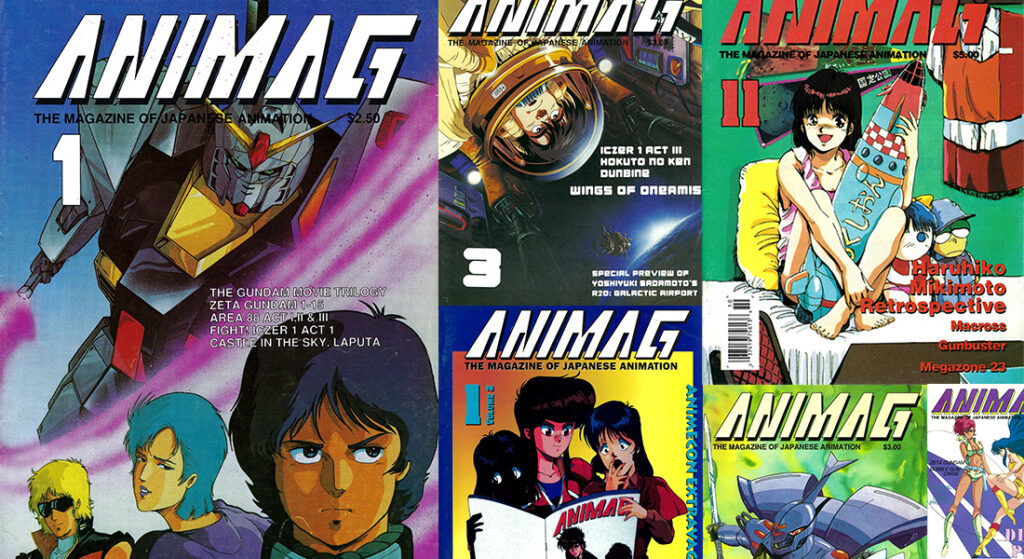

Scans of Animag offer a slightly different perspective on early anime fandom; one of an emerging movement away from pure fanzine and newsletters towards professional efforts. Animag was by no means the first attempt at an English-language anime magazine (that was probably Anime-Zine), but it was the first one that took an earnest stab at professional standards, layouts, and distribution. It also predated the earliest subtitled releases by AnimEigo and US Renditions by nearly three years.

It should also come as little surprise then that much of the staff of later era Animag issues would make their way over to Animerica when it was launched by Viz in 1993. While Animerica established itself as the premier English-language anime magazine of the decade (thanks in no small part to being published by Viz), Animag laid the foundation for all similar magazines that would arrive in the years to come.

But Animag didn’t come out of an established publisher and instead began with fans as writers and editors doing their best to put forward a sense of professionalism and integrity. Claude J. Pelletier, the editor and publisher of Protoculture Addicts (a contemporary fanzine-turned-magazine that came out of Canada) described his own publication as a “fan magazine” and I think its safe to describe Animag similarly.

Like most English-language anime publications of its time, early issues of Animag leaned heavily on summaries of TV episodes or films, reflecting a time when fans were largely consuming anime without any subtitles. The first issue debuted in 19871 with a striking full-color Zeta Gundam cover by Schulhoff Tam. Inside were features on Area 88, the original Gundam series and films, and Zeta Gundam. While I don’t think episode summaries hold much value today, revisiting the series they focused on can help newer fans understand what folks were interested in and what was being circulated on video tape.

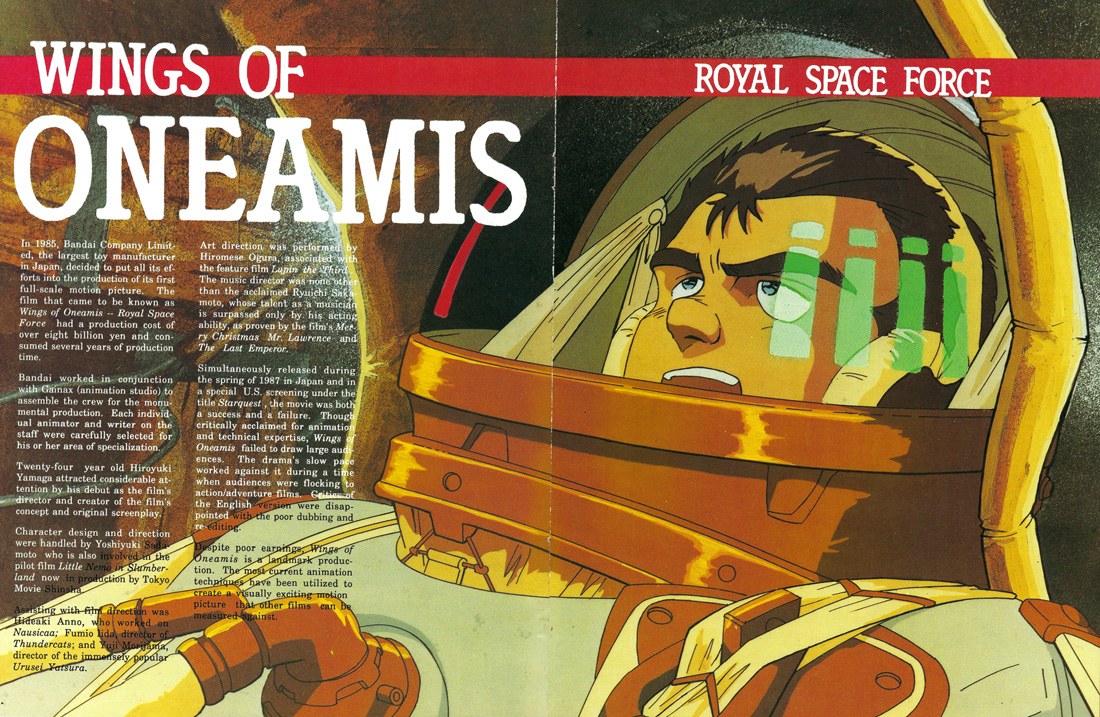

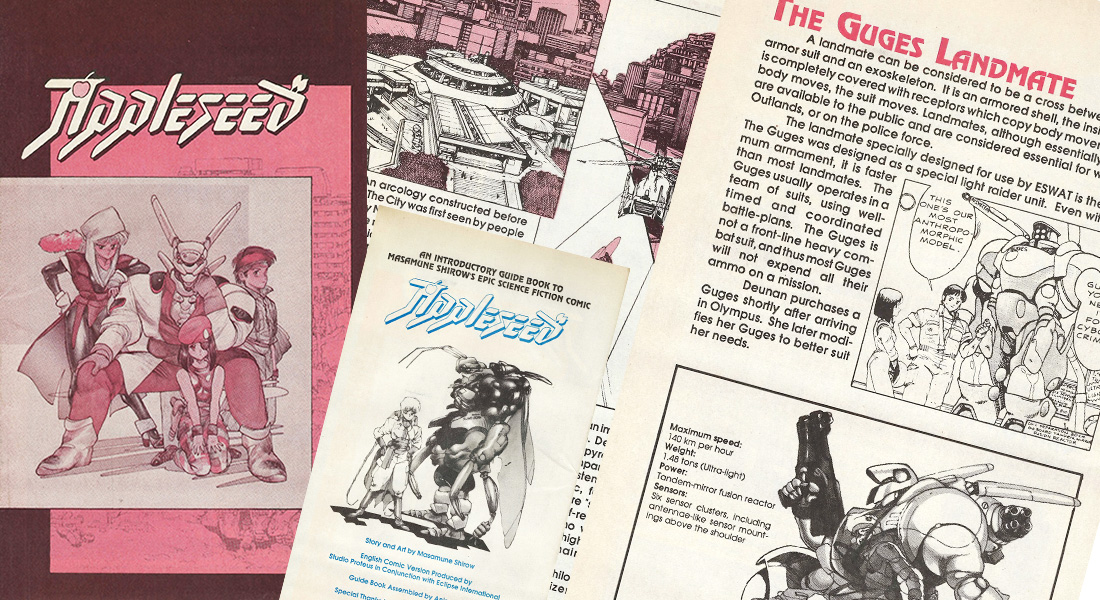

In later issues the magazine’s focus broadened and expanded into features that were far more interesting and worth revisiting today. Vol. 1. No. 3 had articles by Toren Smith about the never-made Gainax film R20: Galactic Airport and interviews with staff from Royal Space Force. Vol. 1 No. 5 included a separate pamphlet that served as a guidebook to Masamune Shirow’s Appleseed manga of the sort you’d see in Japanese magazines. In later volumes you could find an interview with legendary manga artist Leiji Matsumoto, articles about plastic models, a massive Five Star Stories feature, articles about Osamu Tezuka, and an interview with voice actor Maria Kawamura.

Another aspect of Animag that’s worth mentioning was its geographic origin in California’s Bay Area. With mail and long-distance phone calls bringing fans across the country together–albeit expensively–I’m not sure that folks appreciate how regionalized much of fandom still was in the late ’80s. Animag was able to take advantage of the plethora of shops in both the Bay Area and Los Angeles. Flip through an issue of Animag and you’ll get a good idea just how many shops in California were catering towards anime fans back then. Names like Kimono My House, Nikaku Animart, Japan Video, and Newtype Hobbies will sound very familiar to those who were fans in the Bay Area during the 1990s or those who did mail order (just about all of these shops did mail order).

The Bay Area was also the home to AnimeCon ’91 and the early years of Anime Expo and Anime America, representing a sort of cultural nexus in fandom at a time when anime conventions were occurring all over the country but few had the guests and connections of those three related events. Purely speculative on my part, but if I had to guess those same connections may have gotten Animag that Haruhiko Mikimoto cover for its 11th issue.

After Animag’s first year, the magazine was in a different place. Trish Ledoux (future founding editor of Viz’s Animerica) had become the magazine’s editor and as of Vol. 1 No. 5, the magazine was published by Pacific Rim Publishing. The new publishing partnership seemed to bring a noticeable increase in paper quality and represented yet another unusual nexus Animag and Bay Area anime fans found themselves in the middle of: tabletop gaming.

The Bay Area was, in the late ‘80s, also a hotbed for tabletop gaming. Most relevant to anime fans was R. Talsorian Games, publishers of anime inspired role-playing games like Mekton and Teenagers from Outer Space (and later the hybrid anime/gaming magazine V.Max). R. Talsorian founder Mike Pondsmith was listed as an advisor in early Animag issues and in the mid ’90s his company would publish anime-based RPGs like Bubblegum Crisis, VOTOMS, and Dragon Ball Z.

Pacific Rim Publishing also published another anime-adjacent magazine called Battletechnology, a licensed Battletech magazine that was written as if it was an in-universe publication from the 31st century. Battletechnology used plastic model kits (which, if you’ll remember, were borrowed from the likes of Dougram and Macross) for photos, reminiscent of the photo novel features seen in magazines like Hobby Japan and Model Graphix. Pacific Rim Publishing still exists today but they’re focused on historical wargames with no giant robots in sight.

The point of all of this, I suppose, is if you’re curious about anime fandom of the late ‘80s right before those first steps towards a professional licensed anime industry took root in the US, it’s worth your time to flip through scans of Animag. Many of the folks who contributed to the magazine played a major part in both the ‘90s anime industry and anime fandom, both of which helped set the stage for the post-Toonami anime reality we all live in today.