It’s kind of inconceivable to me that in September this site will be celebrating its tenth anniversary. I’ve been pretty bad about mentioning the anniversaries, but ten years feels like it’s big enough to justify celebrating. The concept for this particular article dates back to the earliest days of Zimmerit when I was creating lists of articles I’d like to do for the site. Features on “The Dull Mediocrity of Gall Force,” “The 1980s OVA Power of Lost Planet 2,” and one about early anime mods for Duke Nukem 3D and Doom never really got underway, but I’m happy I finally got around to organizing this one.

Direct-to-video anime was a format that really helped set anime apart. The original video animation format allowed unusual ideas to flourish, creators to experiment, and offered up the perfect mix of length and shock value to help jump start the anime licensing industry in the English-speaking world. OVAs (or OAVs, if you’re of a particular age) offered a new way to commercialize anime and make money off an older subset of anime fandom following the implosion of the early ’80s gunpla boom.

The format was derided early on as being without much actual value; video shelves held plenty of middling manga adaptions, unnecessary sequels, uninspired originals, and outright, low-budget pornography. But the format had its gems. After kicking around for a year or two, by 1985 the format was starting to show its strengths and establish itself as a format for interesting stories.

To celebrate the site’s anniversary and to encourage folks to go looking in the video bins of history, I reached out to a range of folks to hear about their favorite OVAs. I asked them to write about an OVA they loved. Not necessarily their favorite or even one that was easy to recommend, but a single OVA that they loved. The following article consists of what was shared with me.

I also hoped that the way I framed this project would encourage folks to avoid the obvious titles and focus on the stranger, more unpopular stuff. The list below does that pretty well and presents an interesting slice of OVA history that runs pretty much for the entire length of the format. Huge thanks to everyone who participated in this little exercise.

If you have a personal favorite that didn’t get mentioned here, write us a quick comment below to let us know about an OVA you love.

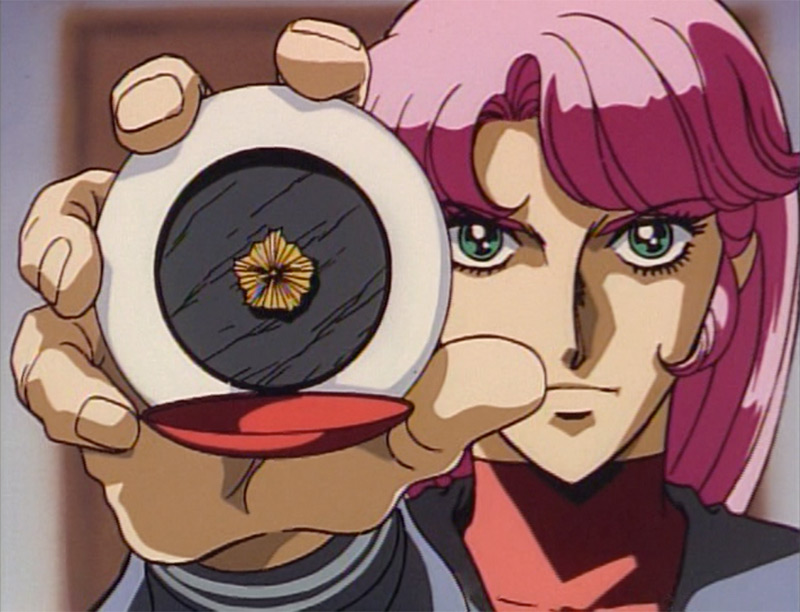

SUKEBAN DEKA [1991]

I’ve always been in love with the concept of the bloody, trashy, action-filled 90s OVA. Within that decade, there’s a wide swathe of titles to choose from—be it something like Cyber City Oedo 808 or Kite. However, there’s one two-part series that’s been on my mind lately: 1991’s Sukeban Deka. An adaptation of Shinji Wada’s manga, this one-hundred-minute romp follows pink-haired delinquent Saki Asamiya as she investigates the brutal girl gang who’s taken over her old stomping grounds.

It’s not the greatest series I’ve ever seen, but I’m enamored with how it combines classic anime direction with exploitation film sensibilities. It might sound a touch reductive, but there were moments where I thought, “Is this what you’d get if Osamu Dezaki directed a pinky violence flick?” From the exploitation flick revenge plot, to the many postcard memories, and the cool-as-hell femme fatales, Sukeban Deka feels like a slick synthesis of both film making forms. Though with those pinky violence influences in mind, the series requires the same sort of heads up I’d give while recommending those films. Namely, intense sexual violence and involuntary drug use. But if you’re able to stomach that, I think you’ve got a pretty rad movie night ahead of you.

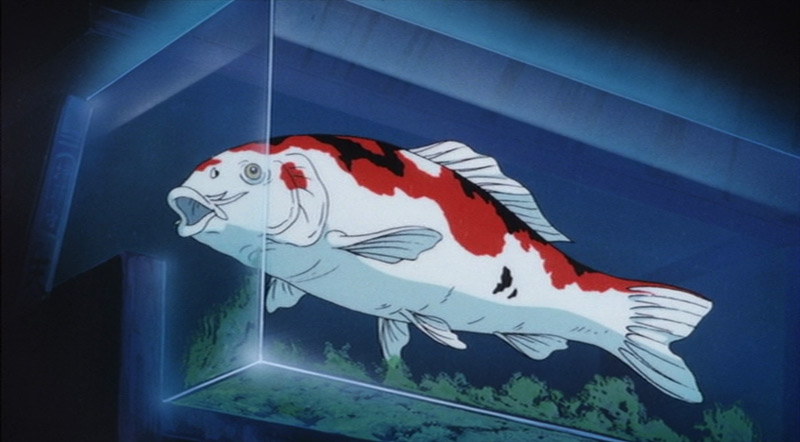

TWILIGHT Q: MYSTERY ARTICLE FILE 538 [1987]

The second of two episodes of Twilight Q (the first, “Time Knot: Reflection” is also interesting but more conventional), Mamoru Oshii’s “Mystery Article File 538” shows how just a few years after Dallos, the OVA had morphed from a format adjacent to TV anime but with a little more violence and titillation to a medium with titles ranging from mega-franchises like Bubblegum Crisis to indulgent, artsy one-offs like this one.

Landing between Angel’s Egg and Patlabor in Oshii’s filmography, the 30-minute “Mystery Article File 538” takes place during a sweltering Tokyo summer in which airplanes are spontaneously turning into carp in midair, a mystery one detective suspects might have something to do with a ramshackle apartment and its weirdo residents.

Told largely through grainy black-and-white images and narration, it owes an obvious debt to Chris Marker’s La Jetée, but it’s packed with Oshii’s particular obsessions—the dubious nature of memory, the ever-changing landscape of Tokyo, down-and-out middle-aged detectives, instant noodles—not to mention a haunting Kenji Kawai score and tack-dry sense of humor. It almost feels like a trial run for the stuff he would go on to do packed into one wonderful, enigmatic 9,000-yen tape.

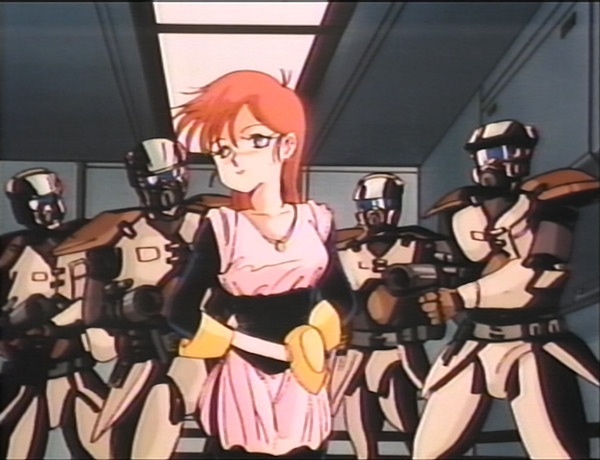

COSMOS PINK SHOCK [1986]

Cosmos Pink Shock is a bubbly, tongue-in-cheek sci-fi mini-adventure—a 1980s OVA time capsule packed with animated style, impactful visuals, and charismatic ship designs. In just 30 minutes, it stitches together flashy animation, satire, and teen passion. Its rushed abruptness may leave you craving more—but for a brief, vibrant blast of 80s anime, it’s a fun and unique find.

AREA 88 [1985]

I’ll consistently state that the greatest OVA of all time is Giant Robo: The Day the Earth Stood Still, while accepting if others answer Legend of the Galactic Heroes, Aim for the Top: Gunbuster, or Macross Plus. There’s already been an entire zine devoted to how great Patlabor is. But the OVA I love remains the first subtitled anime I ever saw, so many decades ago: 1985’s Area 88. Kaoru Shintani’s tale of a civilian airline pilot unwillingly conscripted to fight as a mercenary in the Middle East combined sweeping melodramatics of characters who looked and behaved like shojo romantics with maniacally detailed illustrations of environments and fighter jet combat. The peak “bubble economy budget” cel animation, the vocal tracks by the queen of anisong herself MIO (now known as MIQ), the audacity of the violence and the shocking—initially anger-inducing!—finale combined to be something so far beyond American animation of that era that there was no turning back from the otaku path after seeing it, especially since right before I’d seen the goofy English dub of Riding Bean. I was in sixth grade. Something tells me sixth graders nowadays might be watching tamer Japanese cartoons as their introduction!

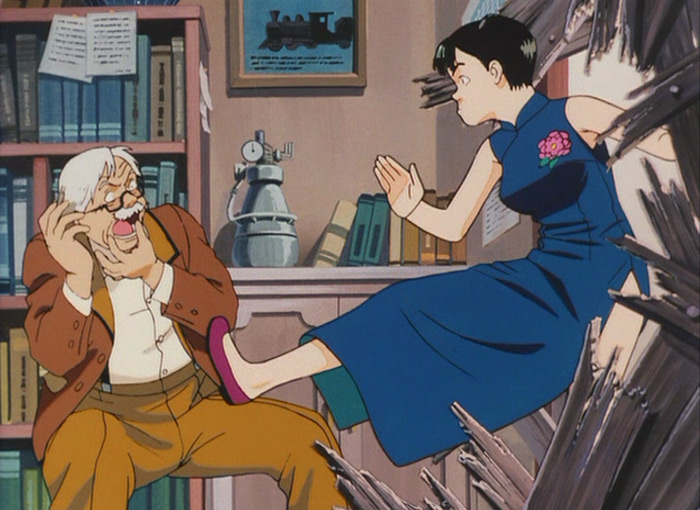

SPIRIT OF WONDER: CHINA-SAN NO YUUTSU [1992]

Delicate. Evocative, Evanescent. Not words I usually associate with steampunk, but words that fit this gorgeous little OAV beautifully. It’s about straight people but it could easily be called yaoi in the sense that it has “no climax, no point, no meaning” – there’s a plot, but no resolution. The point is the beauty of individual moments and individual relationships; like life, where the story arc rarely resolves itself, but far prettier and as sweet as your first heartbreak.

If you like English seaside towns, the Victorian era, Cavorite and girls whose no-nonsense manner reveals the core of steel inside the flower, this is for you. If you like things happening fast and plots that explain all the details and tie up all the ends, it isn’t.

It has stayed with me when many more popular OVAs have faded from my memory. Victorian poet Robert Browning wrote “If you get simple beauty and naught else, you get about the best thing God invents.” This is what he was talking about.

MACROSS II [1992]

It’s safe to say that Macross II is not a beloved series within the fandom–and yet I love it nonetheless. Long ago, I purchased Manga Entertainment’s movie edit on VHS, making it my first exposure to “real” Macross after having previously watched Robotech. It had all the essential elements of a Macross series: Cool transforming robots, a love triangle, and catchy pop songs. And I dug its unabashedly ’90s stylings in its depiction of the future. Was it better than what came before it or since? Nope. Did Shoji Kawamori have any input on it? No, but that doesn’t make it any less valid as a Macross series. We all have comfort food that we love, and to me Macross II is the mecha equivalent of mac ‘n cheese. It’s no filet mignon, but it gets the job done. In other words, Macross II is a perfectly cromulent mecha anime.

RIDING BEAN [1989]

The Chicago courier known as Bean Bandit will transport you or anything you want for a fee, and not a cheap one. But when someone tricks Bean into being part of a sophisticated scheme he and his partner Rally Vincent get mad, and Bean is not someone you want to anger especially if there is money and a kid involved. Then toss in a vindictive police detective out to get Bean, nods to American car chase films, references to the Blues Brothers, classic cars, and a large variety of identifiable firearms there is a lot going on here. Plus Sonoda got Megumi Hayashibara to say some pretty dirty lines.

DOWN LOAD: NAMI AMIDA BUTSU WA AI NO UTA [1992]

1992’s Down Load: Nami Amida Butsu wa Ai no Uta is not just an “OVA I Love,” but also “Why I Love OVAs,” providing a platform for its creative talents to do something odd and special without the constraints of theatrical or television animation. Studio Madhouse’s tie-in to a pair of PC Engine games combines the unique talents of director Rintaro with those of legendary animator and designer Yoshinori Kanada to produce a breezy, beautiful, and irreverent 45 minutes of cyberpunk animation all set to an eclectic bluegrass/rockabilly soundtrack.

Certainly, its gang of young punks led by a man on a futuristic red motorcycle confronting a conspiracy is familiar to fans of classic cyberpunk anime. However, it differentiates itself with strikingly simplified, expressive squash and stretch animation in conjunction with an overall lighter tone and bawdy sense of humor that reflects Lupin III more than Akira, all while still providing the excellent, dense visual and mechanical design that characterizes some of the best cyberpunk anime videos. Down Load is a highly distinct work and a great companion to Rintaro’s similarly exceptional 1987 effort Take the X Train that I can’t recommend enough to those willing to seek it out.

GOSENZO-SAMA [1989]

In an era of weird, engaging projects, Gosenzo-sama Banbanzai! (‘Long Live the Ancestors!’) still stands out, with a style that tries in animation to imitate theatre, especially puppet theatre, and with a few elements that reflect wittily on VHS as a format. Its dry and rather bleak strain of humour won’t suit all tastes, but it deserves a look!

RE: CUTIE HONEY [2004]

Who was it really that said “too much of a good thing can be wonderful?” Mae West? Liberace? I think it was Cutie Honey. Re: Cutie Honey is a 2004 three part OVA, with each episode helmed by a different anime luminary: Hiroyuki Imaishi, Naoyuki Ito, and Hideaki Anno, each indulging in their unique proclivities/cliches as they put their spin on Go Nagai’s cybernetic heroine. You can definitely see the gears turning in Imaishi’s head as he tries ideas here that would get expanded on in Panty & Stocking. And Hideaki Anno’s episode feels oddly like a rough draft of Shin Godzilla, as a gigantic purple creature spews projectiles out its back and the American government waits with baited breath to drop an A-Bomb on Japan.

This was one of the first anime I ever torrented, and I waited 20 years(!) to get a home video release in the states (thanks, Discotek). Seeing it in HD reminded me how kinetic, how unabashedly ribald this OVA is. Action, a color pallet to die for, over indulgence of nudity, it’s a lovingly crafted, cloyingly bubbly cheesecake. Despite being very firmly rooted in Go Nagai’s Showa era escapades and being 20 years old now, this OVA still feels fresh, even if a lot of characters have flip-phones.

Stars to the heavens! Flowers to the earth! Love to humanity!

GOSOHOGUN: THE TIME ETRANGER [1985]

During the golden age of the OVA, stark creative expression could spring from unlikely sources—one of the most notable examples of this being, to me, 1985’s GoShogun: The Time Etranger. Ostensibly a sequel to a smartly written but still fairly standard super robot television anime, it abandons its titular mecha and exchanges its light-hearted tone for an experimental narrative that delves into themes of mortality and metafiction. Centering on the GoShogun team’s lone heroine, Remy Shimada, Time Etranger is a probing character study with psychological thriller and horror elements; I have to imagine fans were at least a little surprised by the genre shift, even given writer Takeshi Shudo’s reputation for the shocking plot swerve in Minky Momo. The result is a work that defies easy categorization. Strange, ambitious and heartfelt, it’s hard to imagine it coming into existence outside the very specific era from which it hails. I find some fresh detail or angle of interest upon every rewatch, and am always trying to net it new viewers. I feel like every person I get to give Time Etranger a watch helps Remy endure somewhere out there on her journey through endless time.

– khoda

BLUDGEONING ANGEL DOKURO-CHAN [2005]

Bokusatsu Tenshi Dokuro-chan (Bludgeoning Angel Dokuro-chan) is an anime that opens with a reference to George W. Bush having a WiFi device hidden under his suit during the 2004 presidential debate against John Kerry, immediately followed by a joke about then North Korean dictator Kim Jong-il. And that’s before it launches into its bread and butter gag of the titular “Bludgeoning Angel” Dokuro killing the main character, Kusakabe Sakura, in cold blood for walking in on her while changing, exposing comical amounts of blood along with internal organs and brain matter. It’s okay–because she’s a magical angel, he gets better with one simple spell.

The 2000s were filled with lots of cliched moé content and Dokuro-chan took those cliches to their logical conclusions in grand fashion. If the typical harem hero got punched into the air, Sakura got brutally murdered. If the typical harem heroine had some fake “cute” personality, Dokuro-chan was intentionally irritating, causing (typically fatal) trouble just for the hell of it. Based off of a light novel series that ran for 11 volumes, I can guess that the original work starts to take itself seriously, but the initial 4-episode OVA adaptation from 2004 is just a fun and stupid comedy that’s too-hot-for TV. The 2007 follow-up is okay, but already demonstrates the series’ diminishing returns with its heavy focus on sexual titillation over making you laugh. The first series is a keeper, though.

– wah

GUNDAM UNICORN [2010]

In 2010, the Universal Century had essentially been out to pasture for over a decade, and the US anime DVD bubble had recently burst. Then suddenly, there was Gundam Unicorn – a high profile OVA set three years after Char’s Counterattack, and being sold internationally with a well-made, day-one English dub! The excitement was palpable at the time, and I still remember the fans’ energy for every new episode trailer with a lot of fondness.

These days though, as someone with a love for Unicorn, I reflexively feel the need to qualify my appreciation. Its story shakes out to a treasure hunt for a prize that can’t mean anything. The revelation of Laplace’s Box could never have been the epoch-changing event the characters thought it would be, because at the end of the day Unicorn is a story being told within an established chronology.

But If you’ll forgive the cliché, Gundam Unicorn is about the journey, not the destination. It somehow manages the magic trick of being a CCA sequel/spinoff full of Gundam ZZ references and obscure mobile suit cameos that’s nonetheless still accessible to newcomers. The stubborn idealism of Banagher Links quickly cemented him as one of my favorite leads in the franchise. Hiroyuki Sawano’s landmark score set the stage for him to define the sound of 2010s anime. Oh, and the robots look great too, with Hajime Katoki delivering a mix of refined versions of familiar designs with new, iconic MS that feel right at home in UC 0096.

I still love Gundam Unicorn, and it’s not just that you had to be there. Probably.

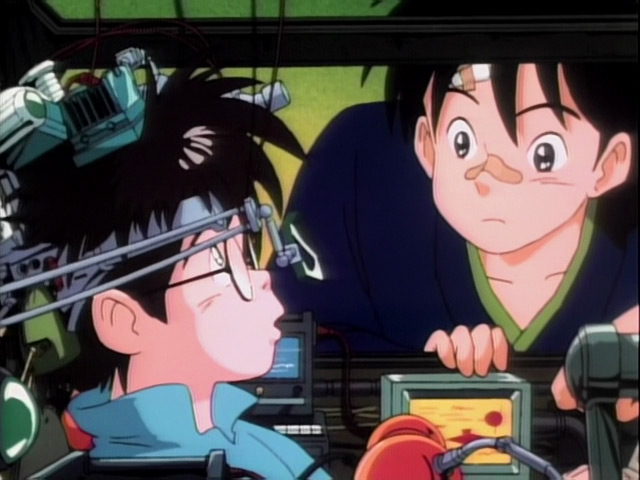

MOBILE POLICE PATLABOR: THE EARLY DAYS [1988]

Where the Patlabor animated films were crisp, clean and largely serious refinements of Headgear’s speculative fiction, the franchise’s original seven-parter was anything but. Rough and ready animation and scattershot story lines; suffice to say, Mobile Police Patlabor: The Early Days remains the epitome of a first draft. However, the fledgling series remains a true gem, and the appeal of later outings were sown in 1988-89.

While the AV-98 Ingram is as arguably iconic as anything from Macross or Gundam, Patlabor’s true strength is in its examination of bureaucracies and PR, of liabilities and human relations.

The Early Days OVA is a lighthearted test bed for stories that would be sharpened in later releases, but the conceit of a bungling special vehicles unit that borders on doing more reputational or physical damage than their adversaries, in machines often deemed too expensive or dangerous to operate remains a breath of fresh air.

While the later animated TV Series enjoyed room to flesh out its gaggle of misfit police officers, The Early Days provided a short and sharp, if appropriately uneven, snapshot of the Patlabor world. A true diamond in the mechanical rough.

PATLABOR: THE NEW FILES [1990]

Originally released as bonus episodes alongside the VHS and Laserdisc releases of Patlabor the Mobile Police: On Television, the New Files are a delightful and sometimes bewildering addition to the original series. The freewheeling style of the original series–which swung between situational comedy, mecha action, and character drama–is only amplified here. The New Files features ghost stories, an Ultraman parody, and my favorite episode in both series, “The Seven Days of Fire,” in which a crackdown on pornography turns SV2 into a totalitarian state.

Part of The New Files’ charm is that it feels like a celebration of Patlabor itself, a chance for the staff of the original series to let loose and have some fun. At no point, however, does the show lose sight of its characters, and the relationships which form the emotional core of the series. For as much as The New Files is used as an opportunity to bring back one-off characters and try out some more out-there plots, it also contains some genuinely touching and thoughtful episodes. In many ways, The New Files is a condensation of all the charm and foibles that made the television series so beloved.

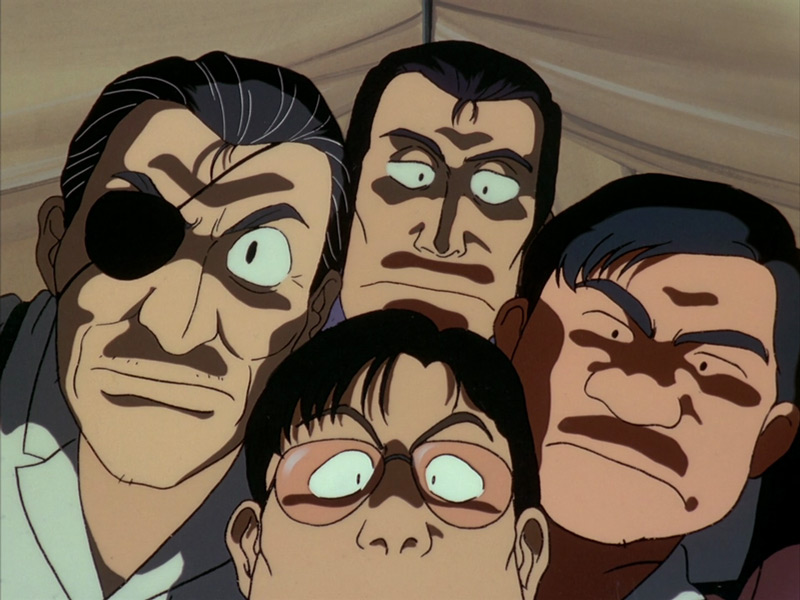

MAHJONG HISHŌ-DEN: NAKI NO RYŪ [1988]

This three-episode OVA by Satoshi Dezaki, via Magic Bus studio and a very young Gainax, first comes off like one of those “highlight reel” adaptations where they animate all of a manga’s most important scenes in a row, creating a context-less project only appreciable by existing fans.

But when you go to the source material, you’ll see that Naki no Ryu is just like that, burning through the background table-setting of gangland hits and yakuza warfare as fast as it can. The real concern of this comic is to portray, as stylishly as possible, one extremely cool guy sitting at the mahjong parlor table working his magic. This adaptation plays it straight, adding in just a few 80s laser effects, along with the memorable afterimage of the hero’s lit cigarette as his hands move.

A surprisingly visually striking work considering its genre, Naki no Ryu is carried by its atmospheric depictions and its charismatic hero, “The Calling Dragon” (voiced by Shuichi “Char Aznable” Ikeda). He’s slumped over the table with his shades and his cigarette hand obscuring his expressionless face, silent except to cryptically foretell his opponents’ doom, and handling his tiles with the flair of a stage magician. The Dragon moves his hands with such slow-motion, after-imaged drama that we might call these “special moves” in a world otherwise entirely devoid of such fanciful notions.

The Dragon’s favorite catchphrase is “there’s soot on your back”: a cryptic portent of doom. In the mindset of this series, luck is something you have or you don’t, and when it leaves people, its absence stains them forever. Unluckiest of all are the endless procession of mob bosses who want to own our hero and conquer the gambling underground: they all end up bleeding out while the Dragon strolls out into the night to a bit of mournful jazz. Roll credits.

DEVILMAN: THE BIRTH [1987]

When I first saw 1987’s Devilman: The Birth, you know, the one about confused high schooler Akira becoming the devil-fighting Devilman after possession by the demon Amon while at a wild psychedelic freakout, I was fresh out of high school and dead certain I wanted more. Is this why the OVA format exists, to deliver slick late ’80s updates to grungy 70s icons? Final proof came with the 1990 sequel Devilman:

Evil Bird Sirène, delivering all the demon-destroying payoff The Birth promised. Eschewing the ink-splattered anarchy of Go Nagai’s original Devilman manga as well as the Toei monster hijinks of the 70s TV anime, these two OVAs were helmed by character designer Kazuo Komatsubara and his Oh Production studio. The animation is smooth and the backgrounds and characters grounded in realism, all the better with which to invade normalcy with tentacled horrors, shotgun blasts, and the bare-bosomed fury of Sirène, madder than hell and ready to destroy Devilman and everything else within a fifteen mile radius. By the time Devilman: Evil Bird Sirène’s conclusion expressed itself across the ripped devil-flesh of its title characters, we realized this Japanese animation WAS for kids–the outlandish fever dreams of the kids we’d been in 1972, now all grown up.

ZONE OF THE ENDERS: 2167 IDOLO [2001]

There’s something to be said about the unassuming, but rock-solid OVA. In the realm of mecha anime, the Gunbusters and 0080s tend to dominate discussions of the medium, but there are a host of competently-made series that don’t reinvent the wheel and are better off for it. And for our money, Zone of the Enders: 2167 Idolo ranks at the top of that list.

Originally released as a pack-in bonus for the JP-only “Premium Package” version of the first game, Idolo tells the story of Radium Lavans, the hotheaded pilot of the eponymous Orbital Frame. A Martian native, Lavans chafes against the prejudices he routinely experiences by his supposed Earth betters, channeling that anger into and through his mecha.

Produced at the tail-end of the industry’s reliance on cel-animation, Idolo looks great. The animation is detailed and smooth, buoyed by a moody and memorable score. By the end of its 55-minute runtime, it hits a lot of genre talking points, but it never fumbles the messaging or overstays its welcome.

People should watch Idolo.